UNILATERAL EXTENSION CLAUSES IN FOOTBALL CONTRACTS

1. INTRODUCTION

Unilateral extension clauses are widely used in the football industry. Frans de Weger, the current chairman of FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber (hereinafter referred to as: “DRC”), defined these clauses as follows: “The extension option is the right of the player and/or club to extend the period stipulated by the parties in an employment contract1”.

The definition has a straightforward practical approach and reflects the entirety of the aim of these clauses. Notwithstanding the evolution of DRC and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (hereinafter referred to as: “CAS”) jurisprudence, for the sake of a complex review of the topic, these clauses may also be defined as clauses entitling one party in the contract to prolong the duration of the contract in the event that reasonably predictable events, agreed by the parties, arise in objective reality, which were at the moment of signing the contract unenforceable for the parties (hereinafter also referred to as: “UEC”). Practice shows that these clauses are mainly drafted in favour of the Club.

Whilst the reasons for offering unilateral extension clauses may vary, the legal grounds for it are not regulated by FIFA at this stage, thus leaving room for such regulation by national associations or domestic labour legislation of the country concerned. Thus, the issues falling under the present subject are related to employment relations which have international dimension.

Such reality makes difficulties for FIFA judicial bodies or independent sport arbitration to properly assess the legality of such clauses in case-by-case scenarios, which can have serious impact on the quality of adjudication. Eventually, in 2006 in one of its landmark cases2 , CAS established several requirements, which unilateral extension clauses must comply with. Noteworthy to mention, that those criteria have also been developed by the same CAS in another case3. The analyses of those awards will be covered later in this thesis.

At this stage, it is of a paramount importance to mention that despite the efforts of CAS to establish a non-mandatory but effective guideline for the parties to follow while concluding contracts with unilateral extension clauses, there is no any mandatory regulation at the international level. Essentially, “Portmann criteria” sets 5 criteria for the parties to comply with:

- “The length of the maximum possible duration of the employment relationship is not excessive”;

- “The renewal option must be exercised within an acceptable deadline before the expiry of the current employment”;

- “The player is not at the mercy of the club regarding the content of the employment contract”;

- “The salary reward arising from the option right is defined in the original contract”;

- “The option will be clearly established and emphasised in the original contract so that the player is conscious of it at the moment of signing the contract”;

For the sake of completeness, the developed 2 other criteria by CAS will also be added to this list for complete overview:

- “The extension period should be proportional to the main contract”; and

- “It would be advisable to limit the number of extension options to one4”.

A comprehensive review is to be conducted between unilateral extension clauses and the principle of proportionality, reciprocity and pacta sunt servanda applied in the industry, existing jurisprudence, and regulations. Afterwards, it will be possible to draw a conclusion in line with the existing regulations.

2. UNILATERAL EXTENSION CLAUSE IN FOOTBALL CONTRACTS

The notion “football contracts” includes a wider scope than the employment contract only. In the present thesis only the employment contract shall be reviewed within the scope of unilateral extension clauses application.

2.1. Types of Unilateral Extension Clauses

UEC was developed within the practice in the football industry, so the establishment of its typology must be based on practical experience (empiric method), considering the recommendations and principles, embedded in the jurisprudence. Beforehand, it’s noteworthy to mention that unilateral extension clauses is a type of extension clause. It is mandatory to review the UEC through the scope of contractual stability, enshrined in article 17 of FIFA Regulations on status and transfer of players, 2023 May edition (hereinafter also referred to as: “RSTP”)5. Some authors connect the birth of contractual stability with post-Bosman era6, however, the contractual stability was introduced far back in time, in the case Eastham v Newcastle United FC Ltd7.

Consequently, considering the Portmann criteria, the following definition can be provided: subjective application of unilateral extension clauses, objective application of unilateral extension clauses, UEC application in time.

Subjective application. In the context of subjective application, unilateral extension clauses can be classified as bilateral, in which both parties of the contract are entitled to exercise unilateral extension clauses and purely unilateral, in which only one parties is entitled to exercise UEC. However, in the thesis it will be reviewed as drafted in favour of the club as shown in the practice.

Objective application. In the context of objective application unilateral extension clauses can be classified by specific conditions, which are reasonably predictable for the parties, but unforeseeable, in other words – conditional: the contract may be unilaterally prolonged if the player has effective playtime in “N” number of minutes on the pitch during the main contract or, for instance, the club shall significantly increase the salary for the extension period for exercising of UEC or the UEC shall be exercised if the club becomes champion or any other criteria, which the parties can materially or statistically verify, etc. All the objective criteria laid down in the contract should be clearly drafted and emphasized in a manner, so the player shall be conscious of the clause at the moment of signing and the player should not be at the mercy of the club regarding the content of the employment contract, and the Player’s remuneration should be stipulated in the original contract.

Application in time. In the context of application in time UEC the standard is defined to advisably limiting the UEC to one extension, stipulating it to be proportional to the original contract’s duration, which in turn must not be excessive, and to exercise such entitlement within the acceptable deadline before the expiry of the current employment.

Presumably, it can be noted that if the aforementioned formal requirements are met the UEC shall be deemed valid, taking into account the specificities of the case-by-case review for adjudication. Anyhow, as it was said earlier, UEC is strictly bound by the principle of contractual stability. Therefore, the principles such as reciprocity as well as other principles applicable thereto (reciprocity, proportionality, contra proferentem, etc) shall also be taken into consideration.

2.2. Application of the principle of proportionality on Unilateral Extension Clauses

The specificity of UEC is essentially related to the uncertainty of the duration of the contract, therefore the question is how the principle of proportionality is applicable for the assessment of compliance with the fundamental pillar of the modern football industry regulations – contractual stability?

According to Omar Ongaro: “When having to examine such clauses, the DRC, as well as CAS, have constantly confirmed that they need to comply with the fundamental principle of proportionality. If the amount stipulated in the contract appears to be disproportionate, in particular, if compared to the remuneration to which the professional player concerned is entitled to on the basis of the same contract, then the respective compensation may be reduced to a reasonable and appropriate level8.”

Evidently, the issue arises when the potential breach of contract may happen before the exercising of UEC or during the notice period of such exercise. In other words, the problem for proper assessment and application of principle of proportionality is the entitlement of the compensation under the contract containing UEC.

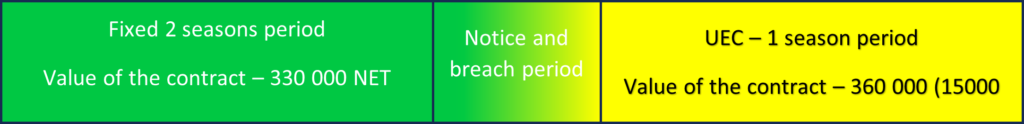

While the compensation under art. 17 of RSTP is clear for the fixed period, the compensation for the period of UEC is unclear and leaves room for ambiguity. In other words, if the clause is drafted in favour of the club and the termination without just cause occurs within the period prior to the exercising of UEC, it is unclear if the extension period covered by UEC shall be taken into consideration or not. This issue can be displayed in the following example:

- The player and the club concluded a contract with a term from 01st of August 2021 until 31st of May 2023 (2 seasons) with UEC to prolong the Contract until 31st of May 2024 (one season) by the Club upon the dispositive notice by the Club to increase the remuneration of the Player by 100% for the period covered by UEC, which must be made within one month until 31st of May 2023.

- Player’s remuneration is agreed 15 000 NET per month (no any compensation is set for unjustified breach).

- No any overdue payables under art. 12bis of RSTP9.

- The club sends a notice of exercising UEC on 03 April 2023.

- The Player received a much more favourable offer from “inducing” club and invokes invalidity of the clause and leaves the club on 31 of May 2023.

- The club files a claim requesting compensation under art. 17 of RSTP (followed by possible counterclaim).

Consequently, in this scenario the total value of the contract for one party, the club, significantly differs from a subjective perspective: for the club it shall be 690 000 Eur NET, for the other, the player – 330 000 Eur NET due to lack of entitlement for the player to exercise UEC. This issue leads to the other: the interrelation between pacta sunt servanda and UEC. Cases with similar factual background are common and are heard by FIFA10.

2.3. Pacta sunt servanda and Unilateral Extension Clauses

The roots of the basic principle of contract law – pacta sunt servanda, arise from the UN Convention on the Law of Treaties, the preamble of which defines as follows: “The States Parties to the present Convention, […] Noting that the principles of free consent and of good faith and the pacta sunt servanda rule are universally recognized11”. The same principle was enshrined in the same convention in article 26: “Every treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith.12” It is one of core principles of contractual stability, which in turn is reflected in articles 13–18 of FIFA RSTP13 upon the agreement between FIFA, UEFA and EU Commission in 200214.

This principle is purely enshrined in art. 13 and 17 of FIFA RSTP and is backed up by longstanding jurisprudence of CAS and Swiss Federal Tribunal (SFT): “agreements have to be executed (pacta sunt servanda) by the parties involved to them15” ; “pacta sunt servanda should not be easily disregarded16” ; “[…] in principle, the doctrine of pacta sunt servanda (which is enshrined in both the FIFA Regulations and Swiss law), which in essence means that agreements must be respected by the parties in good faith, is the guiding general principle […]17”. At first glance, it seems that pacta sunt servanda shall prevail over any law of the country concerned aimed at achieving a unified and global application of FIFA RSTP. According to official FIFA RSTP commentary (November 2021 edition): “Article 13 reflects the fundamental principle of contractual stability and contract law, that contracts must be respected: “pacta sunt servanda.” A specific feature of football employment contracts is that they are always concluded for a predetermined period. The concept underlying all provisions designed to maintain contractual stability is based on this fundamental fact18”.

Summarizing, it is clear that pacta sunt servanda shall prevail as a binding rule of behaviour, which the parties undertake to comply with when entering the contract, unless the other party is able to prove the invalidity of such clause on the grounds of the facts at hand (e.g. art. 20,21,23, 28, 29 of Swiss Code of Obligations).

In this regard, following circumstances shall be taken into account:

- The player is always in less favourable condition than the club (the employer);

- The club as an employer represents the standard form of its contract allegedly in compliance with law of the country of the club and FIFA rules and regulations (possible “contra proferentem”).

Thus, these circumstances and the lack of international regulation leaves a room for disadvantage for the player in the employment relations with the clubs resulting in excessive and abusive, yet legal conduct by the club (bargaining power). The objective is the balancing of interests of the club and the legal protection of the player and vice-versa as it was displayed in the practical example above.

Principle of reciprocity is another core component of contractual stability and is applicable regardless the contract is terminated with (art. 14 of RSTP) or without just cause (art. 17 of RSTP). Omar Ongaro rightfully emphasized that: “The relevant section of the Regulations is based on the principle of reciprocity. In other words, the same behaviour (or misbehaviour) shall, mutatis mutandis, lead to the same consequences, independently of the responsible party (player or club)19”. The same approach is stipulated in the same official FIFA RSTP commentary (November 2021 edition)20. In practice, this principle is commonly applied to the penalty/liquidated damage, buy-out or release clauses upon art. 17 of RSTP.

Gauthier Bouchat rightfully says, that: “since its prime decisions in 2004, the DRC laid the foundation of what would be its constant approach towards the liquidated damages clause. In particular, the DRC held that “the relevant clause being reciprocal, the Chamber agreed that the amount of money stipulated in the contract shall be taken into consideration when establishing the financial compensation to be paid by the club to the player.21” Therefore, the DRC established from that moment onwards that the reciprocity of a penalty clause is the key factor for assessing its validity22. According to the DRC, “reciprocity” does not only mean that the contract must determine the consequences of a breach for each party, but it also requires reciprocity in the calculations stipulated in the contract23.24” However, CAS has deviating approach on this matter in disciplinary cases, particularly in the case CAS 2013/A/3411 Al Gharafa S.C. & M. Bresciano v. Al Nasr S.C. & FIFA, the panel emphasized that: “It is to be noted, in that regard, that Swiss law does not require “penalty clauses” to be “reciprocal” in order to be valid. Therefore, the DRC was not entitled to disregard it, only because it would not apply to a breach committed by Al Nasr(2)25.” It should be noted that both standard of proof and application of several principles may differ in disciplinary cases (vertical disputes) due to peculiarities deriving from the facts presented thereto.

Nevertheless, the essence of compensation, whether it is defined by the contract or is applied on the grounds of art. 17 of RSTP by default, is the same, the party in breach shall be obliged to compensate the party who suffered the loss caused by the breach. Therefore, the principle of reciprocity shall be applied even if there is no penalty/liquidated damage, buy-out or release clause and the standard residual value method of compensation shall be applied.

Wouter Lambrecht rightfully states that: “the situation of a club following an unjustified breach of contract by a player is indisputably not the same as the situation of a player following a breach of contract by a club26” and “the value of the services of a player is therefore never merely represented by the (remaining) value (salary) of his contract27”.

From the regulatory perspective, if the solution is provided in FIFA regulations, the club will have legitimate expectations and certainty (principium certitudinis juris) when entering into contract with the player, granting the club a portion of predictability in the sense of financial planning, thus balancing the interests of both parties.

3. JURISPRUDENCE & LAW

It is well known that the UEC jurisprudence began in 2004 and evolved over the years28. Therefore, the overview of its evolution is extremely important to emphasize the absence of consensus the community has not reached from the business-wise perspective and the contradicting practice by CAS.

3.1. “Portmann Criteria”

The legal perspective (report) provided by Professor Wolfgang Portmann has frequently been used as a reference point to assess the legitimacy of a unilateral option clause allowing a football club to extend a player’s contract. This expert opinion was requested by the FIFA Director of Legal Services in 200729. The background of it will not be reviewed as it is well-known in the industry.

The cornerstone of “Portmann Criteria” lies in its legal substance. It does not reflect the correlation of UEC with FIFA RSTP, it reflects the UEC compliance with Swiss or International Public Policy. The report concluded that they (ed. UEC) “take a form that does not excessively bind the employee30”. Although the report provides the five criteria to follow in order not to violate the aforementioned policy, the issue is that CAS is not bound by Swiss Law and shall decide the dispute according to:

- the rules of law chosen by the parties or, in the absence of such a choice, according to Swiss law in ordinary proceedings (article R45)31 and;

- the applicable regulations and, subsidiarily, to the rules of law chosen by the parties or, in the absence of such a choice, according to the law of the country in which the federation, association or sports-related body which has issued the challenged decision is domiciled or according to the rules of law that the Panel deems appropriate in appeal proceedings (article 58)32.

While the application of law in ordinary proceedings is clear, the appeal proceedings have some peculiarities. This is a complex matter for separate topic of study, nevertheless brief review is needed to break down the obstacles, which CAS encounters when adjudication UEC disputes.

Due to pyramid structure and flowless operation requirement for FIFA to achieve its objectives enshrined in article 2 of FIFA Statutes and the maintenance of contractual stability, established by the agreement between EU commission, FIFA and UEFA, and, finally, taking into account the fact that FIFA is an association registered in the Commercial Register of the Canton of Zurich in accordance with art. 60 ff. of the Swiss Civil Code33, it is of a paramount importance for CAS to achieve unified application of FIFA regulations globally. This statement is proved by the award of CAS, according to which: “Hence, due to the indispensable need for the uniform and coherent application worldwide of the rules regulating international football (TAS 2005/A/983-984, para. 24), the Panel rules that Swiss law will be applied for all the questions that are not directly regulated by the FIFA Regulations (cf. CAS 2005/A/871, para. 4.15)34”.

Noteworthy to mention the Haas doctrine developed by Prof. Ulrich Haas about unified application of the regulations and the impact of article R58 on it, according to applicable regulations shall prevail even where a choice of law of the parties have been made. “if a uniform standard is applied in relation to central issues. This is precisely what Art. R58 of the CAS Code is endeavouring to ensure, by stating that the rules and regulations of the sports organisation that has issued the decision (that is the subject of the dispute) are primarily applicable. For good reason Art. R58 of the CAS Code grants the parties scope for determining the applicable law, and thus scope for changing the legal basis underlying the decision, only subsidiarily35”. This doctrine is backed up by CAS36. Thus, any law chosen by the parties makes it barely academical for the application in the concrete case or at least shall be taken into consideration for comparative perspective.

At first glance, “Portmann criteria” seems to be the part of a uniform standard as 1) it is in line with Swiss public policy (the notion of international public policy shall not be reviewed due to lack of direct enforcement underneath); 2) it sets 5 requirements that the parties must meet aimed to fulfil the principle of legal certainty. Hence, these 5 criteria can be seen as a threshold for the parties, the contravening of which will assure the invalidity of the UEC in the contract, but the formal compliance of these requirements, in turn, does not establish the validity of the clause. This practice introduces an element of unpredictability for the parties when entering into contract, which brings onto the table the need of UEC regulation on FIFA level (uniform worldwide standard). In turn, such regulation may be in conflict with labour law in many countries, which will be covered later, but that conflict cannot be considered as unsolvable subject to tailored drafting of regulation in article 18 of RSTP.

3.2. FIFA DRC & CAS jurisprudence on Unilateral Extension Clauses

Tiran Gunawardena provided excellent compact evolution of the jurisprudence in his article37 summarizing the landmark cases provided as it follows:

- Apollon Kalamarias FC v Oliveira Morais38 – The Panel upheld FIFA DRC’s decision, which stated that: “Unilateral options are, in general, problematic, since they limit the freedom of the party that cannot make use of the option in an excessive manner. Furthermore, such options are not based on reciprocity, since the right to extend a contract is left exclusively at the discretion of one party”. The matter at stake was UEC with 1+4 year format.

- Panathinaikos FC v. S.39 – The Panel set aside the decision of FIFA Player Status Committee. FIFA found second prolongation invalid, however CAS overturned the decision saying that “no jurisprudence known by the Panel declares such options as absolutely void under all circumstances” and adjudicated in accordance with the substance of the case, not the form by reviewing the act of the parties in good faith resulting in violation of pacta sunt servanda and the fact of unequal bargaining power. The matter at stake was 2+2+1 year format.

- Club Atlético Peñarol v Carlos Heber Bueno Suarez, Cristian Gabriel Rodriguez Barrotti & Paris Saint-Germain40 – “Portmann criteria” was introduced. However, it should be noted that the case was not adjudicated in favour of the club for non-compliance with the criteria. However, the par. 68 of the award provide a significantly important opinion for the development of UEC. The unofficial translation is laid down as follows: “The Panel considers that sport is naturally a transnational phenomenon. It is not only desirable but indispensable that regulations referred to the sport at an international level have a uniform and coherent worldwide character. In order to ensure a respect at a worldwide level, such a regulation should not be applicable in a different way from one country to another, due to interferences established by a State Law or a Sporting regulation. The principle of the universality of the application of the FIFA regulations – or of any other international federation – is a need for the legal rationality, security and predictability. All the members of the football family are therefore under the same regulations, which are published. The uniformity that comes from it tends to assure the equality of treatment between all the addressees of such regulations, independently of the countries from which they are…”.

[Emphasis added]

This approach is in line with the Haas Doctrine within the meaning of the application of the law of the country concerned if “Portmann criteria” is reviewed under conjunction of Swiss Public Policy, thus making the regulation of UEC on FIFA level even more required. Evidently, there is no uniform standard. The UEC disputes are adjudicated case-by-case.

Finally, Gremio Foot-ball Porto Alegrense v. Maxi Lopez case41, where the 2 new criteria were introduced, the para. 68 of which provides as follows:

- The potential maximal duration of the labour relationship should not be excessive;

- The option should be exercised within an acceptable deadline before the expiry of the

current contract; - The salary reward deriving from the option right should be defined in the original

contract; - One party should not be at the mercy of the other party with regard to the contents of

the employment contract; - The option should be clearly established and emphasized in the original contract so that

the player is conscious of it at the moment of signing the contract; - The extension period should be proportional to the main contract; and

- It would be advisable to limit the number of extension options to one

Evidently, there is no uniform standard. The unilateral extension clauses disputes are adjudicated case-by-case.

3.3. Unilateral Extension Clause review from Swiss Law perspective

The conjunction of articles 1 (1), 2 (1), 11 (1), 18 (1) and 19 of Swiss Code of Obligations (SCO) explicitly emphasizes that the conclusion of the employment contract is based on voluntary expression of true and common intention of the parties to be bound by corresponding rights and liabilities within the framework of essential terms of rendering services (essentialia negotii) irrespective of any particular form unless a particular form is prescribed by law. Moreover, the article 320 of the SCO follows the above-mentioned line, in particular the plain wording of it provides as it follows: “Except where the law provides otherwise, the individual employment contract is not subject to any specific formal requirement42.”

Saverio Spera in his article questions the enforceability of UEC under Swiss law essentially connected it to the principle of parity (article 335a (1) of SCO for relations employer-employee relations and discrepancies between notice periods (article 347 (3) of SCO) set by UEC regarding termination of the contract and additionally provides the application of the article 347 (3) by local court in concrete case finalizing it with the following thesis: “if the clause leads to over extensive commitment on the side of the employee, it might be considered an infringement of the ordre public and, thus, be deemed null and void.”43

This approach is half-incorrect for the following reasons:

- Comparison between application of law by state law and within lex arbitri may vary. CAS was historically created for the peculiarities related to regulations of sports and as guarantee for its proper legal functioning. Specificity of sports is regulated on fundamental level (article 165 (1) of Treaty of Functioning of European Union44);

- As emphasized in the abovementioned CAS cases on UEC there is no any restriction in FIFA regulations, the opposite – there is emphasizing on the freedom of movement of the player;

- UEC and notice period may seem connected at first glance, but in practical functioning the notice periods are the same as if one party doesn’t exercise UEC, the contract is terminated (mostly upon expiry) for both parties, if the party, which is entitled to UEC, exercise it, the new notice period shall be applied onto prolonged term followed by the extension exercising. However, this approach does not justify or disprove the violation of the principle of parity (reciprocity).

- Finally, “Portmann criteria” was set as the same redline the trespassing of which will trigger the violation of Swiss public policy (ordre public).

Summarizing, it is safe to conclude that UCE is enforceable under Swiss law if it is drafted in compliance with “Portmann criteria” and existing jurisprudence of CAS, despite the contradiction with principle of parity (reciprocity), which in turn is the reason this issue is to be regulated by FIFA. The other aspect is the requirement of respecting the principle of reciprocity, which is undermined by UEC.

4. ABSENCE OF REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

As was described above there is no any regulation on UEC in FIFA regulations, which could bind the parties to conduct in certain way or fulfil concrete requirement. Therefore, the lacuna must be filled in for achieving the uniform standard for this issue.

4.1. Conflict between national law, “Portmann Criteria” and FIFA RSTP

In debates about global sports law vs international sports law Ken Foster states the following: “Global sports law, by contrast, may provisionally be defined as a transnational autonomous legal order created by the private global institutions that govern international sport45”. Despite the compulsory (force) arbitration46 clauses, enshrined in statutes of international sports federations, which result in the enforceable awards upon New York Convention47, FIFA rules and regulations are not positive laws, international treaties, they are rather corporate internal legal acts of legal entity (Association domiciled in Switzerlans), to which the other party is bound upon membership or agreement. Thus, the regulations adopted by FIFA cannot be ratified on domestic level by state, consequently, there is a high chance that RSTP can come into contradiction with the labour law of a specific country. Moreover, according to article 14 (1) (J) of FIFA Statutes (2022 May edition) member associations are bound by to comply with other regulations of FIFA, inter alia, the same RSTP48.

Consequently, article 1 (3) of FIFA RSTP sets the mandatory provisions (mostly – contractual stability), which must be included without modifications in the member association’s regulations, thus leaving no choice for member associations for leverage. In some countries even contractual stability contradicts to the labour law49, therefore, FIFA puts the member association in a situation to face the following choice: to facilitate the reforming of the labour code with the legislative body of the particular country50 or leaving it without reforming with a situation for local stakeholders to live in parallel legal duality, but keeping the legal lever of pressure on the association.

4.2. The requirement to regulate Unilateral Extension Clauses by FIFA

Inter alia, FIFA set an objective to draw up regulations and provisions governing the game of football and related matters and to ensure their enforcement51 and to control every type of association football by taking appropriate steps to prevent infringements of the Statutes, regulations or decisions of FIFA or of the Laws of the Game52. Take into account CAS jurisprudence mentioned above “indispensable need for the uniform and coherent application worldwide of the rules regulating international football” (TAS 2005/A/983-984, para. 24) the regulation of UEC is under direct interest and competence of FIFA to regulate it due to the contradicting jurisprudence we have at hand now. Such regulation would be aimed to eradicate contradictory application of UEC in the football industry. Moreover, the regulation of UEC by FIFA derives from the paramount importance to protect the young players as formally speaking compliance with the “Portmann criteria” is not difficult threshold for the clubs to comply with and, essentially, limit player’s bargaining power.

4.3. Proposed models of Unilateral Extension Clauses and reforms of FIFA RSTP

Taking into account all the above, in particular the principle of reciprocity (parity), proportionality, balance of bargaining power and the aim of uniform and coherent application of the UEC, there are 2 models, which can be used for UEC regulation by FIFA:

- Bilateral model of UEC (both parties are entitled to unilateral extension).

The essence of this model is to balance the bargaining power of the player as well and bring into the action the possibility of club’s liability in the light of contractual stability. Such model derives from FIFA circular 1171, which sets minimum requirements for the employment contract of professional football players. In particular, the par. 1.5 of the minimum requirements, it clearly mentioned that “the agreement defines a clear starting date (day/month/year) as well as the ending date (day/month/year). Furthermore, it defines the equal rights of Club and Player to extend and/or to terminate the agreement earlier. Any unilateral early termination must be founded (just cause). Reference is made to the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players53”.

[Emphasis added]

According to CAS: “although these Circular Letters are not regulations in a strict legal sense, they reflect the understanding of FIFA and the general practice of federations and associations belonging thereto. FIFA Circular Letters are relevant for the interpretation of the relevant FIFA rules.54” Evidently, FIFA has indirectly set the line of bilateral UEC by the approach emphasized in the aforementioned circular.

B. UEC – entitling only the one party to extend the contract with the pre-requisite to fulfil certain actions prior to the extension.

This model can be described as a security measure under contractual stability. For example, if the club wishes to exercise UEC, it must pay the player the remuneration for extension period in advance. If the player wants to exercise UEC it must undertake not to enter into negotiations with other club within six months after the notice period of exercising the UEC, similar to restriction set forth in article 18 (3) of RSTP.

In other words, “each party would have to provide sufficient consideration to the other party in order to have the right to renew said contract”55 rightfully summarized by Juan de Dios Crespo Pérez.

4.4. Coexistence of proposed reforms and article 18 of RSTP

Assessment of the conjunction of article 1 (3) and 18 of FIFA RSTP provides that all the Special provisions relating to contracts between professionals and clubs are binding at national level. At any level, there is a possibility that some of these provisions may contradict with labour legislation in particular country, however, it is noticeable that these provisions derive from unified international labour law standards, such as International Labour Organization conventions and recommendations. Moreover, as was described above it will be in line with the principle of parity set forth in Swiss Code of Obligations, thus it will correspond to the Swiss labour legislations as well.

The above-made research proves that principle of reciprocity (parity) is in line with the jurisprudence of CAS, the threshold of legality is higher than the one set by “Portmann criteria”, therefore, questioning of the developed UEC restriction done on RSTP level in article 18, will have very low chance of success as such development will be in favour of the player by delivering for the latter stronger bargaining power and reciprocal legal protection from the club. Subsequently, it is presumed that any of both proposed models of UEC are in line with the existing legislation and jurisprudence and may be used for filling the lacuna actively used by football clubs.

5. CONCLUSION

UEC was never regulated by FIFA despite the attempts of recommendation set forth in its circular. CAS attempted to develop it by its own jurisprudence. Prof. Portmann drawn up the threshold of the public policy, which the parties should never trespass for the sake of avoidance of the invalidity of UEC. Nevertheless, the absence of regulation leaves room for ambiguity and uncertainty for the parties to comply with in order to achieve the validity of the transaction. In other words, at the moment the industry has clear rules, which trigger the invalidity of the clause (“Portmann criteria”, CAS jurisprudence), but does not have the rules for its validity. This is the fluctuation point, where the problem arises and leaves room for ambiguity and lack of clarity. In short – a lacuna is needed to be filled in.

The absence of the UEC regulation triggers problem in actio stricti iuris for the party and further adjudication. Ad casum both the regulatory and adjudicatory body need explicitly regulated framework for proper functioning. After all, this is needed from the positive law perspective and aiming at achieving the uniform standards of application and further adjudication. One must not forget the old legal doctrine by Lord Hewart – “justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done56”.

This doctrine is recalled by CAS from to time57 and for the purpose of achievement of such high level of standard the industry needs either to establish stare decisis and regulate the issue upon case law or to evolve and develop reforms in RSTP corresponding the needs of the industry within its practical functioning. It was demonstrated that there are legal principles under the concept of contractual stability, which serve as fundamental pillars, on which the whole system is built on, thus the amendments must be strictly in line with these principles in order not to jeopardize the jurisprudence carefully tailored by CAS within these years. Consequently, the proposed models of UEC regulations can be taken into consideration by FIFA, whilst considering that one of those derives from their own circular.

Such regulation will serve as framework for establishment of future uniform standard for application of UEC by clubs and, rarely, but yet still by players and will help to solve ambiguity arising thereof.

Taking into account FIFA’s role and objective enshrined in its own statutes, it is in FIFA’s interests to regulate this issue internationally as soon as possible to modernize RSTP and update it in line with the current practices within the industry.

By Ashot Kyureghyan

- de Weger, F. (2016). Unilateral extension option. In: The jurisprudence of the FIFA dispute resolution chamber. ASSER International Sports Law Series. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. Page 164. ↩︎

- TAS 2005/A/983&984 Club Atlético Peñarol v. Carlos Heber Bueno Suárez, Christian Gabriel Rodríguez Barotti & Paris Saint-Germain, award of 12 July 2006. ↩︎

- CAS 2014/A/3852 Ascoli Calcio 1898 S.p.A v. Papa Waigo N’diaye & Al Wahda Sports and Cultural Club, award of 11 January 2016. ↩︎

- CAS 2013/A/3260 Grêmio Football Porto Alegrense v. Maximiliano Gastón López, award of 4 March 2014, ↩︎

- FIFA regulations on status and transfer of players. 2023 May edition, article 17 ↩︎

- Duval, A. (2016). The FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players: Transnational Law-Making in the Shadow of Bosman. In: Duval, A., Van Rompuy, B. (eds) The Legacy of Bosman. ASSER International Sports Law Series. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. Page 97-98 ↩︎

- Boyes, S. (2013). Eastham v Newcastle United FC Ltd [1964] Ch 413. In: Anderson, J. (eds) Leading Cases in Sports Law. ASSER International Sports Law Series. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. Page 78-79 ↩︎

- Ongaro, O. (2016). Maintenance of contractual stability between professional football players and clubs – the FIFA regulations on the status and transfer of players and the relevant case law of the dispute resolution chamber. In: Contractual Stability in Football. European Sports Law and Policy Bulletin 1/2011. Sports Law and Policy Centre, Italy. Page 44. ↩︎

- FIFA regulations on status and transfer of players. 2023 May edition, article 12bis ↩︎

- FIFA DRC, decision of 7 February 2014, FPSD – 6843 ↩︎

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969. Entered into force on 27 January 1980. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1155, p. 331/Page 2 ↩︎

- Ibid, page 11. ↩︎

- FIFA regulations on status and transfer of players. 2023 May edition, article 13, 14, 14bis, 15, 16, 17, 18 ↩︎

- Siekmann, R.C.R. (2012). International professional football law: Webster, Matuzalem and De Sanctis—The CAS Transfer ‘Buy-Out’ Rulings. In: Introduction to International and European Sports Law. ASSER International Sports Law Series. T.M.C. Asser Press. The Hague. Pp 272-274 ↩︎

- CAS 2008/A/1568 M. & Football Club Wil 1900 v. FIFA & Club PFC Naftex AC Bourgas, Award of 24 December 2008, par. 18 et seq. ↩︎

- CAS 2005/A/973 Panathinaikos Football Club v. S., Award of 10 October 2006, par. 25 et seq. ↩︎

- CAS 2017/A/5213 Genoa Cricket and Football Club v. GNK Dinamo Zagreb, Award of 15 December 2017, par. 39 et seq. ↩︎

- Commentary on the regulations on the status and transfer of players. FIFA. 2021. Page 104 ↩︎

- Ongaro, O. (2016). Maintenance of contractual stability between professional football players and clubs – the FIFA regulations on the status and transfer of players and the relevant case law of the dispute resolution chamber. In: Contractual Stability in Football. European Sports Law and Policy Bulletin 1/2011. Sports Law and Policy Centre, Italy. Page 33. ↩︎

- Commentary on the regulations on the status and transfer of players. FIFA. 2021, Page 106 ↩︎

- FIFA DRC, decision of 10 June 2004, no. 64133.3 ↩︎

- FIFA DRC, decision of 7 February 2014, no. 0214233 ↩︎

- FIFA DRC, decision of 27 November 2014, no. 1114067 ↩︎

- Bouchat G. Liquidated damages clauses: a critical analysis of the jurisprudence of the dispute resolution chamber and the Court of Arbitration for Sport. In: Football Legal. N 9 – June 2018, Special Report: Termination of Players’/Coaches’ Contracts. Page 70. ↩︎

- CAS 2013/A/3411 Al Gharafa S.C. & M. Bresciano v. Al Nasr S.C. & FIFA, award of 9 May 2014 par. 95 et seq. ↩︎

- Lambrecht W. Contractual stability from a club’s point of view. In: Contractual Stability in Football. European Sports Law and Policy Bulletin 1/2011. Sports Law and Policy Centre, Italy. Page 100 ↩︎

- Ibid, page 101 ↩︎

- de Weger, F. (2016). Unilateral extension option. In: The jurisprudence of the FIFA dispute resolution chamber. ASSER International Sports Law Series. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. Page 164. ↩︎

- Pestana Amaral F. (2016) The validity of a unilateral extension clause in favour of the football club ↩︎

- Crespo J. Maintenance of contractual stability in professional football general considerations and recommendations. In: Contractual Stability in Football. European Sports Law and Policy Bulletin 1/2011. Sports Law and Policy Centre, Italy. Page 340 ↩︎

- Code of Sports-related Arbitration, 01st of February 2023, article R45 ↩︎

- Ibid. article R58 ↩︎

- FIFA Statutes, article 1 ↩︎

- CAS 2008/A/1517 Ionikos FC v. C., award of 23 February 2009, page 13, par. 7 ↩︎

- Haas U. (2015). Applicable law in football-related disputes – The relationship between the CAS Code, the FIFA Statutes and the agreement of the parties on the application of national law. In Bulletin TAS / CAS Bulletin, 2015/2, p. 11-12 ↩︎

- CAS 2017/A/5374 Jaroslaw Kolakowski v. Daniel Quintana Sosa, award of 10 April 2018, page 11, par. 65, 66 ↩︎

- Gunawardena T. (2022). Unilateral extension options in football contracts: Are they valid and enforceable? – In: www.lawinsports.com ↩︎

- CAS 2004/A/678 Apollon Kalamarias F.C. v. Davidson Oliveira Morais, award of 20 May 2005 ↩︎

- CAS 2005/A/973 Panathinaikos Football Club v. S., award of 10 October 2006. ↩︎

- TAS 2005/A/983 & 984 Club Atlético Peñarol v Carlos Heber Bueno Suarez, Cristian Gabriel Rodriguez Barrotti & Paris Saint-Germain, award of 12 July 2006. ↩︎

- CAS 2013/A/3260 Grêmio Football Porto Alegrense v. Maximiliano Gastón López, award of 4 March 2014 ↩︎

- Swiss Code of Obligations, SR 220. (30 March 1911 (Status as of 1 September 2023), article 320 ↩︎

- Spera S. (2017) The Validity of Unilateral Extension Options in Football – Part 1: A European Legal Mess. ↩︎

- “The Union shall contribute to the promotion of European sporting issues, while taking account of the specific nature of sport, its structures based on voluntary activity and its social and educational function”

Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union OJ L. 326/47-326/390; 26.10.2012 ↩︎ - Foster, K. (2012). Is There a Global Sports Law?. In: Siekmann, R., Soek, J. (eds) Lex Sportiva: What is Sports Law?. ASSER International Sports Law Series. T.M.C. Asser Press. The Hague. Page 37 ↩︎

- Pechstein and Mutu v. Switzerland, App. Nos. 40575/10 and 67474/10, Eur. Ct. H.R. (2018) ↩︎

- UNCITRAL – Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards. New York. 1958 ↩︎

- Member associations have the following obligations […] to comply fully with all other duties arising from these Statutes and other regulations. ↩︎

- According to the article 112 of the Labour code of Armenia, the employee can unilaterally terminate the contract any time prior one month notice. Article 238 and 239 of the same code provides that the liability of the employee can arise only from the damage if the employee operates with material goods and the damage was caused by operations of such goods (damaging service car, property of the employer, etc). ↩︎

- Many countries have positive obligation to develop sports undertaken on constitutional level. ↩︎

- FIFA Statutes (2022 edition) article 2 (C) ↩︎

- Ibid Article 2 (D) ↩︎

- FIFA Circular no. 1171, Zurich, 24 November 2008, page 2 ↩︎

- CAS 2015/A/3981 CD Nacional SAD v. CA Cerro, award of 26 November 2015, page 11, par. 63 ↩︎

- Crespo J. Maintenance of contractual stability in professional football general considerations and recommendations. In: Contractual Stability in Football. European Sports Law and Policy Bulletin 1/2011. Sports Law and Policy Centre, Italy. Page 340 ↩︎

- The King v. Sussex justices. ex parte Mccarthy. 1924. 1 K.B., page 259 ↩︎

- CAS 2014/A/3630 Dirk de Ridder v. ISAF, award of 8 December 2014, page 21, par. 109 ↩︎

In addition to our article on sports governance, we represent our next article.